Against the “silent crisis” of global biodiversity loss, a people-centred approach to Africa’s protected areas offers hope for people and planet.

More than 130 million tourists a year will visit Africa by 2030 (more than double today’s numbers), lured by its astonishing natural assets. This growing demand turns Africa’s network of national parks and protected areas into a huge economic opportunity. And it strengthens the argument for protecting the unique ecosystems that the parks encompass: ecosystems on which the lives of more than 60 percent of rural Africans depend.

But Africa’s national parks are not what they were. In many countries, their natural assets have been drastically eroded over decades by global demand for illegal products such as ivory and tropical hardwood. This damage has been compounded by local demand for bushmeat and land, fuelled by growing populations in and around the parks who are faced with little or no economic alternatives than unsustainable extraction of park resources.

The landmark global assessment on biodiversity published earlier this month made devastating reading. More than a million species are threatened with extinction. The living bonds that hold the natural world together are unravelling and the current global response is catastrophically insufficient. And it is the African continent – where the needs of a billion more human inhabitants will need to be met over the next three decades – where many questions on the future of the earth’s fragile ecosystems will be answered.

Is it possible to meet the needs of local people who depend directly on a park’s natural assets, and to restore and protect that ecosystem at the same time? Bold park restorations around the continent are showing that it is. The answer lies in a people-centred approach to restoration, one that invests heavily in livelihoods and security for local people, and that attracts the backing of a range of committed funders and investors. SYSTEMIQ is partnering in just such a park restoration in a remote corner of western Zambia, in what would be an historic effort in the country’s growing conservation efforts.

Putting people at the heart of restoration.

Securing Africa’s tourism market could have a transformational impact on people’s lives across the continent. More than 30 million jobs can be directly and indirectly supported by tourism in a decade’s time – more than 6% of the total workforce. However, the drastic erosion of Africa’s natural attractions may present the most significant threat to realising this potential.

Inspiringly, several recent projects have managed to turn ecologically depleted national parks into economically and socially sustainable ecosystems, bringing huge benefits to local communities and national economies. Just over a decade ago, Malawi’s land-based national parks were almost entirely devoid of wildlife and tourists. Today, following a rigorous programme of park restoration, Malawi’s wildlife is thriving once more and Forbes magazine places the country among the top 15 destinations worldwide to visit in 2018. In conflict-hit countries, the stability, security and economic boost gained from restoring a national park can be equally striking: Chinko, a recently restored national park in the Central African Republic, is now the country’s largest employer outside the capital.

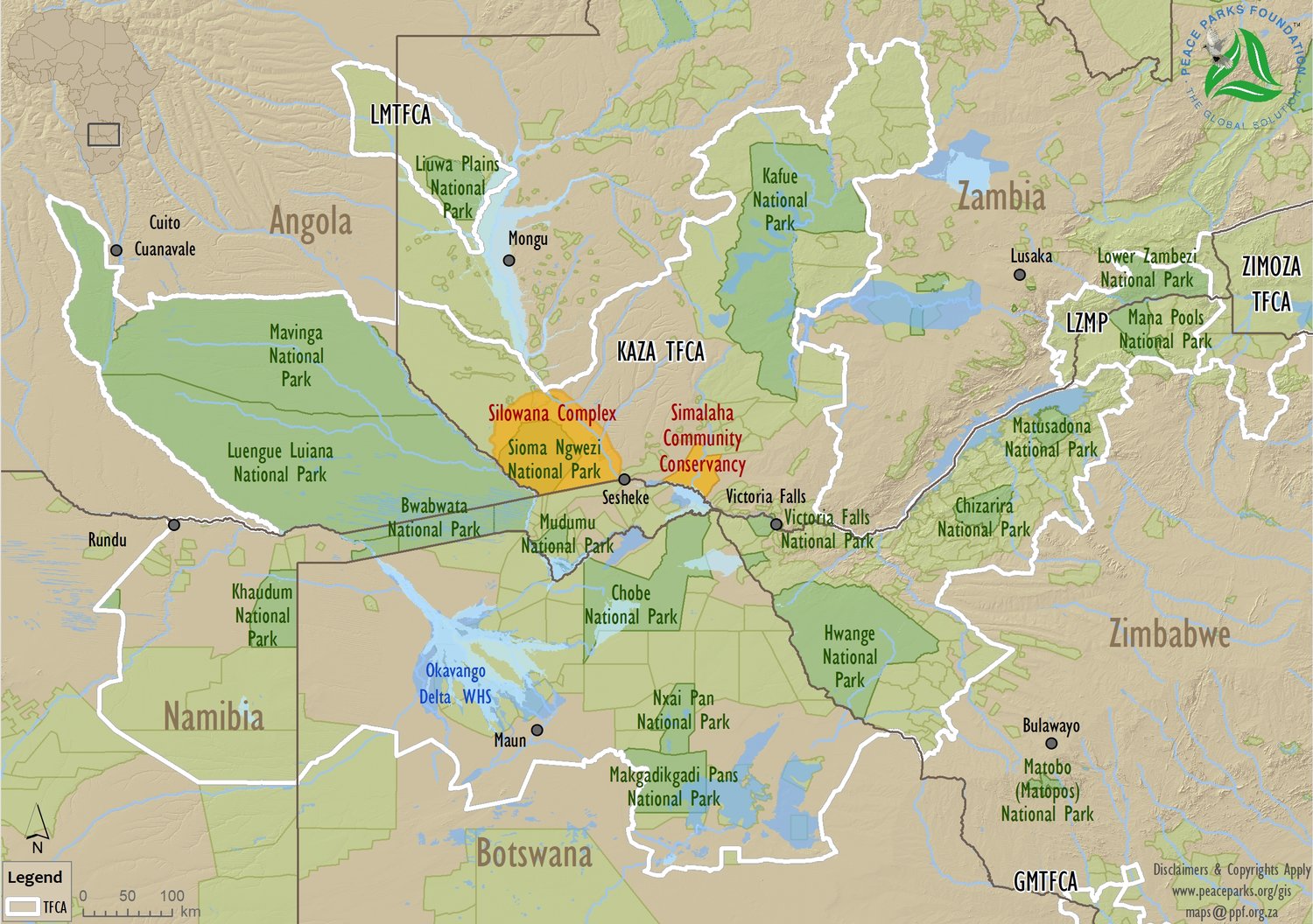

Restoring a park calls for investment in the infrastructure and on-site management capacity. Long-term regeneration and protection depends on providing local people with livelihoods more attractive than depleting park resources. This people-centred strategy is now being pursued in Sioma Ngwezi, a remote park in southwest Zambia lying within the vast Kavango-Zambezi, the world’s largest transfrontier terrestrial conservation area. The Zambian Department of National Parks has formed a new partnership with two NGOs experienced in park regeneration and management – Peace Parks Foundation and WWF. The partnership governance includes leaders from the Barotse community as well as from national and provincial government, the private sector and NGOs. SYSTEMIQ provides strategic support, and links with international funders and investors.

Reversing a tragedy of the commons.

Sioma Ngwezi’s history is typical of many depleted African national parks. Abundant in wildlife, pristine forest and fresh water when the park opened in the 1960s, the park’s 5,000km2 and its immediate environs, a protected Game Management Area (GMA), were well able to sustain the traditional hunting and subsistence farming of the local Barotse people. But external and unsustainable demand for park commodities (such as bushmeat, ivory, and timber) combined with illegal settlement in the park by refugees fleeing conflict in neighbouring Angola have taken a heavy toll. Poaching, logging, and subsistence farming were the best available livelihoods for the ~50,000 people settled in the GMA or seeking refuge in the park. Over time, their combined activities eroded the natural resources they relied on, in an all-too-familiar tragedy of the commons.

Wildlife suffered in particular from the continued destruction. Sioma Ngwezi’s elephant population declined faster than any other on the continent, with just 48 surviving at the lowest point. This decline and the park’s remote location have previously made it unattractive to tourists. Better stocked, more accessible parks on the continent attract as many as 1,000 times more visitors a year than Sioma Ngwezi, and as much as 5,000 times more revenue per unit area.

A people-centred restoration plan.

For decades, international investment has been almost entirely absent from the park. But recent construction of nearby transport links, in Zambia and neighbouring Angola and Namibia, have turned Sioma Ngwezi into a clear candidate for the people-centred restoration proposed by the new park partnership.

Central to the partnership’s plan is to generate employment and livelihoods that beat the economics of illegal poaching, bushmeat hunting and park encroachment. This depends on local people believing in the merits of the plan, embracing and owning it. Only then will they contribute their essential knowledge and skills to protect the park. An extensive local consultation and engagement process has been ongoing for more than 6 months and will complete within the year.

The twin pillars of the restoration plan are tourism and sustainable, legal hunting. Both use land in ways that allow continuous ecosystem protection, and support local jobs and livelihoods. Re-zoning areas in and around the national park will allow three main types of economic activity to thrive: ecotourism in a pristine, regenerated but smaller national park; legal private wildlife hunting in surrounding buffer zones; and subsistence agriculture in development zones, supported by modern techniques to improve productivity and reduce environmental degradation.

Opportunities for different types of funders and investors.

Realising the plan requires long-term investment in re-introducing, protecting and restoring the area’s wildlife and landscapes. It also needs investment in infrastructure to support ecotourism and sustainable hunting.

Given the project’s requirement for long-term finance, the bulk of investment in the early years is likely to come from overseas development agencies and thematic ‘impact’ investors. As this initial investment bears fruit, it will create more and more opportunities for conventional international and local private investors ranging from stakes in individual lodges, to land concession leases to support tourism-related services – food production, transport, construction.

Over the coming months, SYSTEMIQ will be evaluating the portfolio of funding and investment opportunities that surround the plan and working with appropriate investment partners: development banks, development agencies, international impact investors, philanthropic investors and local and regional tourism operators.

Regenerating Africa’s depleted national parks is a complex, systemic challenge which demands effort from all involved. It needs authentic local ownership and leadership of the renewal strategy; world-class protection and management of the natural assets; long-term investment from organisations that understand the ‘development multiple’ they represent; and commercial investment from entrepreneurs who recognise the resulting business opportunities.

The people-centred approach to regeneration in one far corner of Zambia is part of a much wider vision for ecosystems that is shared by governments, NGOs, communities and SYSTEMIQ. It is a vision that turns Africa’s extraordinary network of protected areas into a resource for sustainable economic growth across the continent, and the prosperity of its people and the safety of its wildlife. Together, committed investors and their partners can help to turn the tide on the earth’s silent crisis.