The climate, biodiversity and pollution crises demand global solutions. A new report argues that the European Green Deal can only succeed if it’s linked to green transitions worldwide, and creates new international relationships.

If the European Green Deal is to succeed, the EU must drive sustainable economic systems and societal wellbeing, at home and internationally, says the International System Change Compass. The new report highlights how energy and material over-consumption in Europe creates an enormous ‘footprint’ in other countries and prevents them achieving their own environmental aims. Meanwhile, Europe’s resource-intensive economic systems – in everything from food and energy to housing and transport – are driving climate change, while failing to fully meet our real social needs.

“Europe needs its global partners”

The European Green Deal is a high-ambition strategy: it recognises that economic development, the fight against the climate crisis and inefficient resource use, and a just transition must all go hand in hand. However, this large-scale policy framework will also change the EU’s relationships with countries that bear the brunt of mass consumption, resource extraction, and environmental destruction.

The report calls for a “system change in international relationships” could work, and invites the EU to “step up and build true partnerships with the low-income countries and the most vulnerable states”.

Taking this initiative is a daunting task: it involves rethinking global finance and industrial value chains, international governance and institutions, and much more.

Part of the challenge for the EU will be to reduce its international resource demand while allowing bilateral trade partners to achieve their own development goals – and avoiding the worst knock-on effects. For example, EU regulations on commodities linked to forest destruction could have a major impact on Côte d’Ivoire, which provides nearly half of the region’s cocoa, but at the cost of ongoing deforestation. EU consumers must move away from ‘fast fashion’ and towards circularity – without worsening conditions for the Bangladeshi textile workers, in an industry built around European demand.

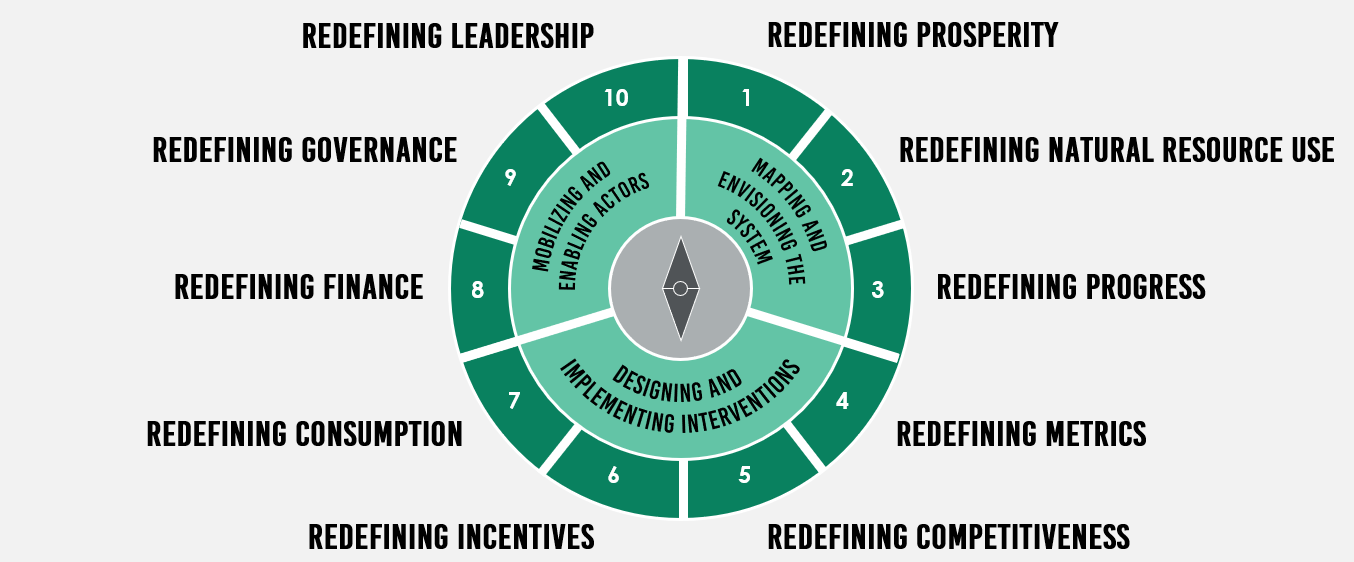

To navigate this complexity, and at the heart of the report, the authors offer the System Change Compass – a guide to reshaping these relationships around shared social and environmental priorities.

The resource efficiency problem – and how to fix it

In overusing Earth’s resources, and by distributing the benefits unfairly, our economic model takes far more than the planet can sustainably give. In recent decades, resource use has significantly improved living standards, in particular in high-income countries. But this now comes at an unsustainable cost to climate, environment and health. Extracting and processing natural resources materials – fossil fuels, metals, minerals, biomass, everything we extract from the Earth – is now responsible for 50% of global climate change.

The problem is that humankind has never separated out economic growth from ever-rising demand for resources. We are now overstepping the planet’s natural boundaries, especially in high-income countries, and locking ourselves out of the safe operating space in which human societies evolved.

“The map of resource use still shows the shadows of an imperialist world, where wealthy nations pursue their ambitions at the expense of others”, explains Janez Potocnik, Co-chair of the UN International Resource Panel. But economic shocks demonstrate how fragile these systems really are. “A more stable and sustainably prosperous future will mean shifting to an era of responsible resource use, where benefits are more fairly shared, mitigating resource fragility and strengthening our resilience.”

Towards a positive vision

However, this is not the first report to call for change. Fifty years ago, the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth made the case for a more sustainable view of prosperity within planetary boundaries. Today, its co-president emphasizes that incremental change – ‘more of the same, just a bit greener’ – will not be enough. “System change goes beyond reducing the negative impacts of the current economic model”, says Sandrine Dixson-Declève. “Instead, it requires changing the resource-driven relationships between high-consuming countries and extracting countries that have long perpetuated unequal consumption patterns and power structures.”

Can this shift to a just global transition succeed? As the report makes clear, this is a huge call for Europe’s decision makers. “It’s not just a shift in thinking about consumption, value chains, and global trade flows, says Heather Grabbe, director of the Open Society European Policy Institute, “but decisive political leadership to create an economic system that meets human needs across the planet.”

Yet recent economic shocks may already be triggering a profound rethink: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has highlighted Europe’s dependence on energy, food and resources from unsustainable sources and unstable regions. The report argues that the EU needs to invest in economic resilience and security, both for itself and its trade partners, by quickly moving towards a sustainable economy and climate neutrality.

And the report’s final word is telling. While so much public and political debate around the green transition centres on reducing negative impacts and limiting harmful activities, we under-value the positive potential for global connections, social cohesion, reduced conflict, and shared resource security. This is not a story about what the EU needs to “give up” to achieve its green and social agenda, but about how it can lead a transition that will benefit the EU and the global community at large.

“International System Change Compass – The Global Implications of Achieving the European Green Deal”, is produced by the Club of Rome, SYSTEMIQ, and the Open Society European Policy Institute.